Debugging Code World Models

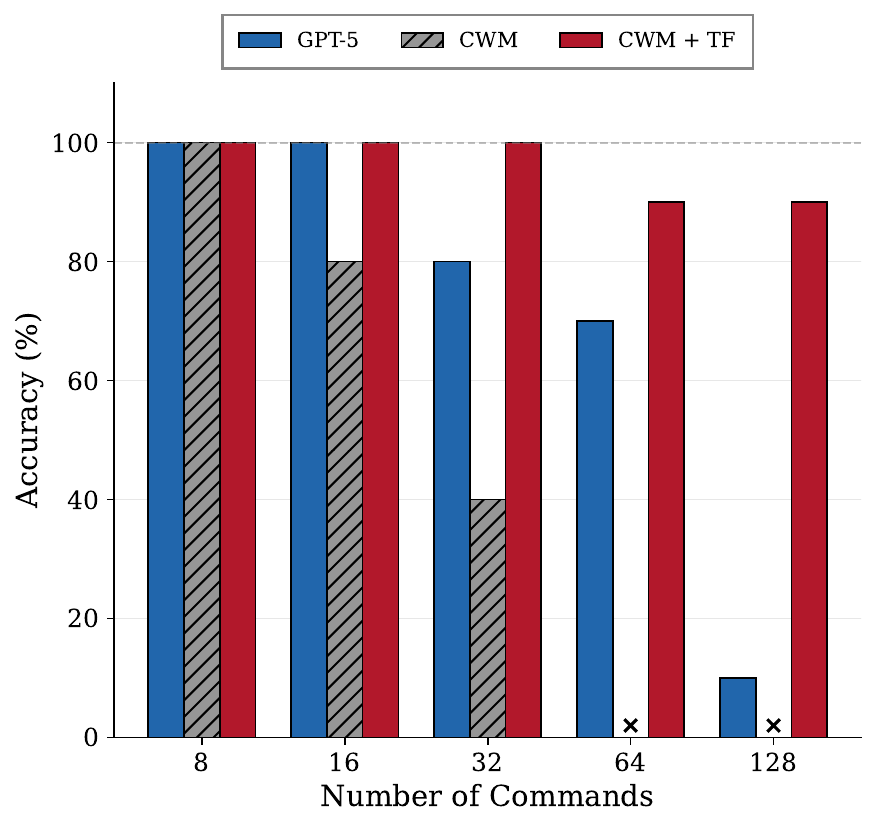

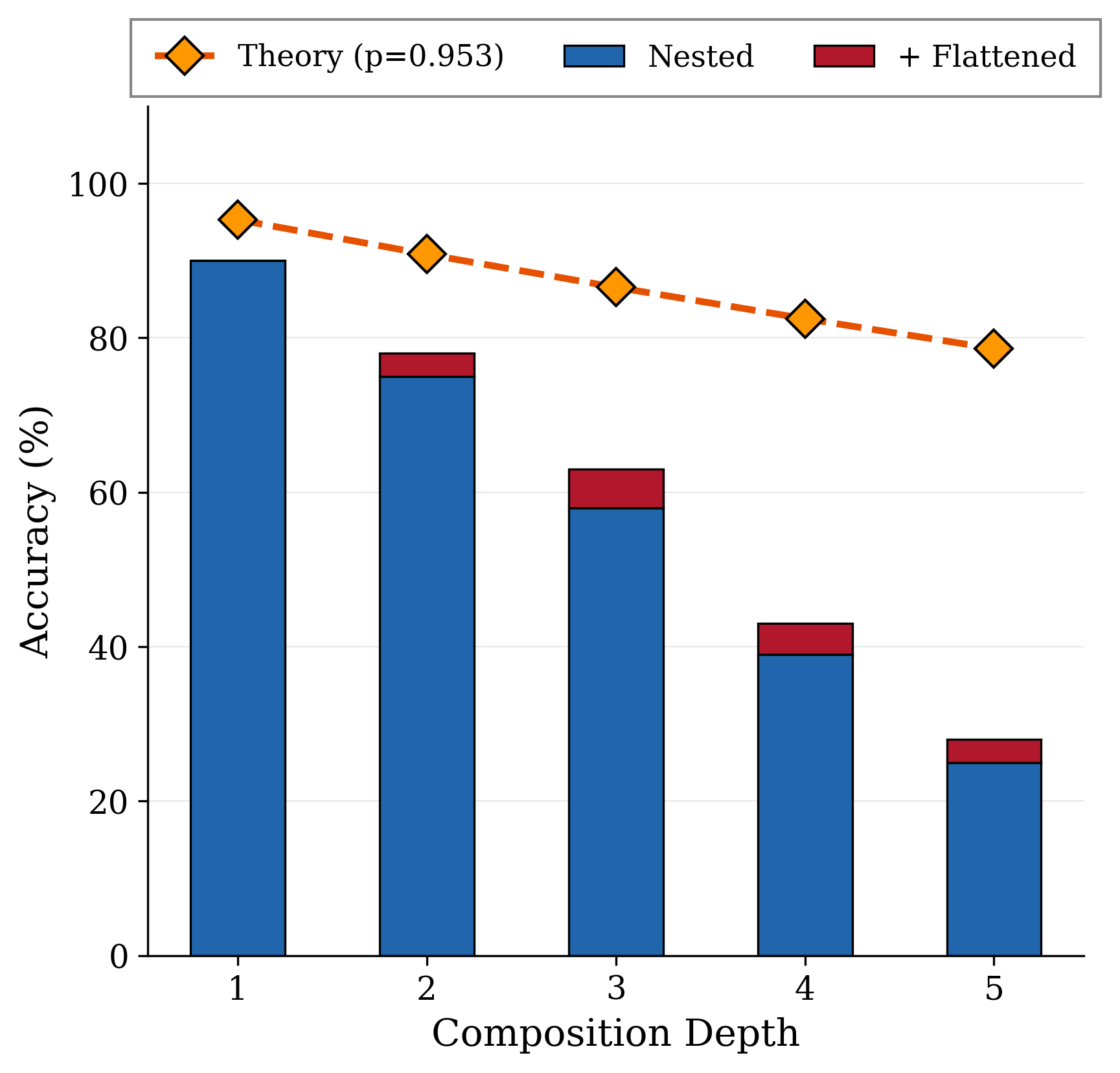

Figure 1: (Left) Accuracy on $S_5$ permutation tracking across sequence lengths (8–128 swaps). CWM baseline generates both commands and states; CWM+TF (teacher forcing) receives ground-truth commands and only predicts states. GPT-5 degrades rapidly while CWM+TF maintains high accuracy, showing the model can track state when given correct actions. (Right) String composition accuracy on nested string functions (depths 1–5). observed accuracy falls far below the theoretical baseline (dashed) computed from atomic accuracy.

1. World Models

World models (WMs) are a framework for prediction (simulation) and planning: you learn a model of how an environment evolves, then you can "roll it forward" to see the result of an action. WMs were first popularized in images/videos, such as Genie [1] in game-like settings where an agent interacts with an environment; the promise is that the agent can learn new abilities by interacting with the learned simulator, enabling more open-ended behavior (e.g., exploration, long-horizon planning, skill acquisition).

Recently, there have been several works that treat language models trained on text as world models, including for text-based games [3], general game playing [4], and code generation guided by MCTS [5][6]. The key difference from a standard language model is the training interface: an explicit action + state format. For example, a code world model (CWM) [2] is trained on traces that look like:

This turns code execution into a supervised "simulate the next state" problem. The CWM paper reports that this kind of training improves downstream performance on software-engineering style benchmarks (e.g., SWE-bench).

The Connection to State-Tracking

This format is closely related to what the model-architecture community calls state tracking, often studied through finite-state automata and long-horizon length generalization [7][8]. Theoretical work has shown that log-precision transformers face fundamental limitations in simulating finite automata [7], while recurrent architectures can represent these transition systems more naturally. Recent work on linear RNNs and state space models [9] demonstrates that careful initialization of recurrence eigenvalues enables reliable state tracking over long sequences. These findings suggest that the choice of architecture, and its alignment with the supervision structure, determines whether models can faithfully track latent state.

World modeling should solve state-tracking. But Transformers can't track state. CWM is a Transformer-based world model. Something has to give...

- Where does it break? On which code patterns does CWM's state-tracking fail?

- Why? What mechanism explains both its successes and its failures?

- Can we fix it? Can we recover accuracy by engineering around the limitations?

- At what cost? What are the efficiency implications for training and inference?

In this post, we use a state-tracking lens to answer these questions.

2. Evaluation on Code Benchmarks

We evaluated CWM on two standard code execution benchmarks: CruxEval-O [11]

(output prediction) and HumanEval [12] (function execution), as well as

the composition (Nesting) dataset [10] that probes compositional execution

of nested string manipulation functions (e.g., upper(replace(strip(x)))).

Table 1 summarizes the results.

Table 1: CWM accuracy on code execution benchmarks

| Benchmark | Samples | Baseline Accuracy | After Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| CruxEval-O | 800 | 85.0% | 90.4% |

| HumanEval | 723 | 91.4% | 92% |

| Composition (string, depth=2) | 100 | 75% | 78% |

| Composition (string, depth=3) | 100 | 58% | 63% |

| Composition (string, depth=4) | 100 | 39% | 43% |

| Composition (string, depth=5) | 100 | 25% | 28% |

About “After Intervention”: In the paper, these numbers come from a small set of semantics-preserving program rewrites applied to failure cases (e.g., expanding nested expressions into explicit temporaries) to test whether errors are driven by hidden intermediate values rather than incorrect execution. This provides a diagnostic sanity check and yields modest gains, but it does not change the core failure analysis below.

These baselines are strong but reveal systematic failure patterns. Error analysis (detailed in the CruxEval, HumanEval, and Composition reports) identifies three primary failure modes: string-valued state brittleness (especially under composition), tokenization discontinuity (string operations breaking token boundaries), and trace truncation (loops generating traces that exceed the 32K token limit). We examine each below.

2.1 Challenge: String Composition

To isolate the source of string-related failures, the paper uses a controlled test based on functional composition: compose deterministic single-argument functions to depth d. This induces multi-step computation without loops or branching, so program structure is held fixed while only the data type varies.

Under this scaffold, CWMs compose reliably across non-string domains: in a multi-domain “Composition Zoo”, CWM reaches 100% accuracy at depth 5 across boolean, bitwise, math, character, list, set, and dictionary categories. In contrast, string-valued compositions degrade sharply with depth under identical structure—implicating representation instability rather than compositional depth.

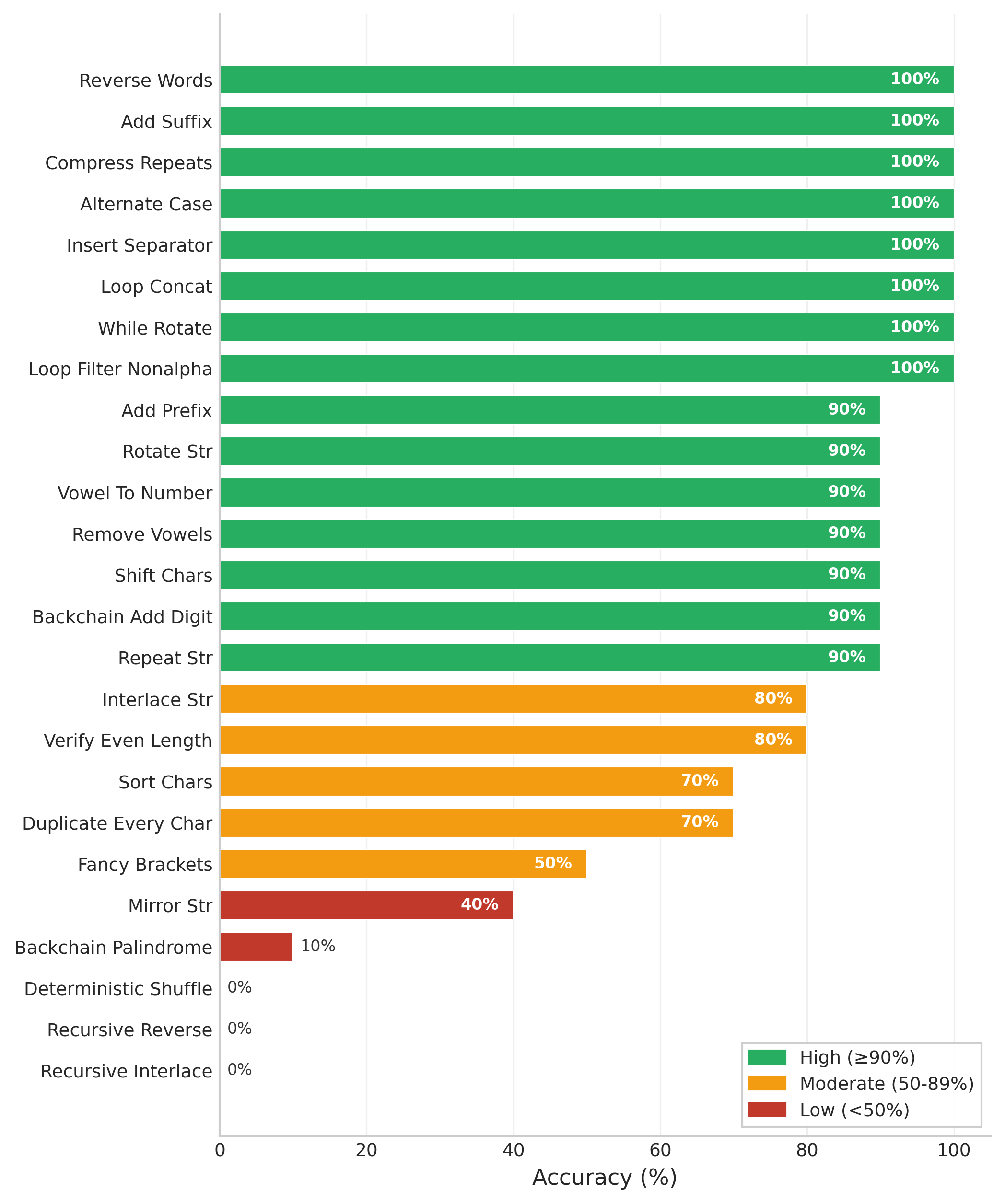

Experimental setup: Using the library of 25 deterministic

string-manipulation functions from the composition string dataset (“Nesting”) [10],

we designed prompts for CWM and first evaluated on atomic (depth-1) calls.

We selected the 15 functions achieving ≥90% atomic accuracy (average: 95.3%),

then generated 100 test samples per depth for compositions from depth 1 to 5

(e.g., depth 3 = func_A(func_B(func_C(x)))).

Figure 3: CWM atomic (depth-1) accuracy across all 25 string-manipulation functions. Functions achieving ≥90% accuracy (above green dashed line) were selected for the composition experiment, yielding 15 high-accuracy functions with average accuracy of 95.3%.

Results: Accuracy degrades sharply with depth—75% at depth 2 down to 25% at depth 5 (Table 1; Figure 1, right)—despite programs being short, deterministic, and purely functional. In stark contrast, non-string compositions maintain 100% accuracy at depth 5 under the same scaffold. This supports the paper’s conclusion that the dominant limitation is string representation, not compositional depth.

2.2 Challenge: Trace Truncation

Dense state supervision has a hidden cost: token explosion. When code contains loops, each iteration generates a full state snapshot. For O(n²) algorithms or large inputs, traces can exceed the 32K token limit, causing truncation before the final output is reached.

In CruxEval, 6 samples failed because their traces exceeded the 32K token limit. An additional 17 samples failed on loop/counter errors, where the model lost track during long iterations even without truncation. Together, these reveal a fundamental tension: the same dense supervision that enables reliable state-tracking also creates traces too long to process.

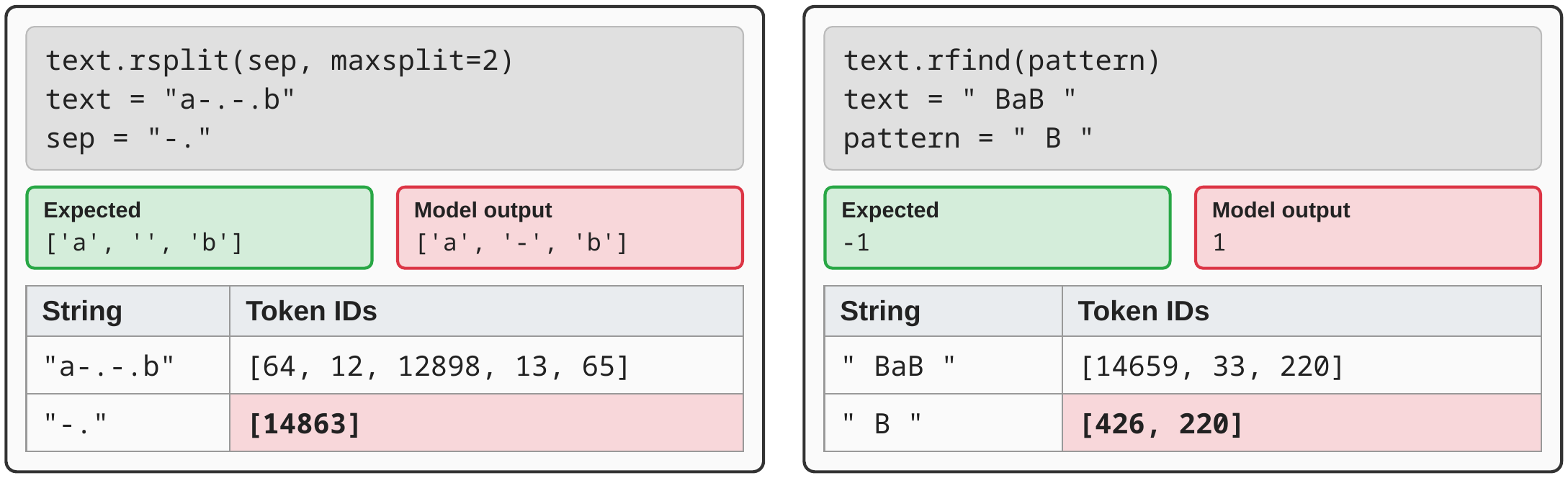

2.3 Challenge: Tokenization Discontinuity

String manipulation creates a challenge unrelated to supervision density: the same character pattern can map to different token IDs depending on context. Under BPE tokenization, a separator or pattern may be a single token in isolation, yet that token can disappear entirely when the same characters appear inside a longer string.

Figure 4: Tokenization discontinuity in string state-tracking.

Under BPE tokenization, the same character pattern can map to different token IDs depending on context.

This can make simple string operations (e.g., rsplit, rfind) unreliable because the token

for a separator/pattern in isolation may not appear in the longer string’s token sequence.

This is problematic for execution: a model operating over tokens may be unable to “find” a separator/pattern at the token level even when the characters exist in the underlying string. This creates brittle errors in deterministic programs and compounds sharply under string composition.

3. A State-Tracking Lens

Why does CWM succeed at state-tracking? The answer lies in its training format: dense state supervision. CWM tracks the state of all variables after each command—what we call reveal spacing = 1. Every operation is followed by a complete state snapshot, creating extremely dense supervision signal.

This raises a natural question: can we achieve reliable state-tracking with sparser supervision? To answer this, we need a controlled benchmark that isolates state-tracking from other code complexities.

3.1 The Shell Game Benchmark

Imagine the classic shell game: three cups labeled A, B, C contain objects 1, 2, 3. A dealer shuffles them by swapping pairs of cups, and you must track which object ends up where. This is exactly what state-tracking requires: maintaining a mental model of system state through a sequence of operations.

$S_n$ in code can be constructed using a variable assignment problem where $n$ variables are initialized with random numbers and then have their values swapped in different commands. We can use print statements for partial reveal that could be used as supervision signals.

Figure 5: (Left) The shell game with three cups representing $S_3$ permutations: each swap changes which object is under which cup. (Right) The equivalent $S_n$ problem as Python code: variable assignments and swaps mirror the cup movements, where tracking the final values requires faithful state-tracking through each operation.

3.2 Evaluation Setup: GPT-5 vs CWM

We evaluated both GPT-5 and CWM on $S_5$ permutation sequences with varying lengths: $N \in \{8, 16, 32, 64, 128\}$ swap operations (Figure 1, left). The task: predict the final values of all five variables.

a=X,b=X,c=X,d=X,e=X. We use a maximum token

limit of 16,384 and evaluate via exact string matching.

View Full Prompts

System Prompt

You are a Python code execution tracer. Your task is to trace through Python code that performs variable assignments and swaps, then determine the final values of ALL variables.

## Task Description

Given a Python function that:

- Initializes 5 variables (a, b, c, d, e) with integer values

- Performs a series of simultaneous variable swaps (e.g.,

a, b, c, d, e = c, e, b, a, d)

You must trace through all the operations step by step and provide the final values of ALL five variables.

## Example

Code:

def execute_repl_trace():

a = 1

b = 2

c = 3

d = 4

e = 5

a, b, c, d, e = c, e, b, a, d

a, b, c, d, e = e, b, c, d, a

def main():

execute_repl_trace()Step-by-step trace:

- Initial: a=1, b=2, c=3, d=4, e=5

- After

a, b, c, d, e = c, e, b, a, d: a=3, b=5, c=2, d=1, e=4 - After

a, b, c, d, e = e, b, c, d, a: a=4, b=5, c=2, d=1, e=3

Answer: a=4,b=5,c=2,d=1,e=3

## Instructions

- Trace through each assignment carefully

- Remember that tuple unpacking in Python happens simultaneously (all right-hand values are evaluated before any assignment)

- Provide the final values of ALL variables in the format:

a=X,b=X,c=X,d=X,e=X - Do not include any explanation, just the comma-separated values

User Prompt (Example with 8 swap operations)

Trace through the following Python code and provide the final values of ALL variables.

def execute_repl_trace():

"""Execute the REPL trace operations."""

a = 8

b = 4

c = 7

d = 8

e = 7

a, b, c, d, e = c, e, b, a, d

a, b, c, d, e = e, b, c, d, a

a, b, c, d, e = b, e, a, c, d

a, b, c, d, e = a, b, e, d, c

a, b, c, d, e = b, c, e, a, d

a, b, c, d, e = e, a, c, b, d

a, b, c, d, e = a, e, c, b, d

a, b, c, d, e = b, d, e, c, a

def main():

execute_repl_trace()What are the final values of all variables? Provide in the format: a=X,b=X,c=X,d=X,e=X

<|trace_context_start|>, <|frame_sep|>,

<|action_sep|>). Unlike GPT-5 which only predicts final values,

CWM generates a complete execution trace with explicit variable states in JSON format

at each step.

View Full Format

CWM Input Format

<|begin_of_text|><|trace_context_start|>

def execute_repl_trace():

"""Execute the REPL trace operations."""

a = 8

b = 4

c = 7

d = 8

e = 7

a, b, c, d, e = c, e, b, a, d

a, b, c, d, e = e, b, c, d, a

a, b, c, d, e = b, e, a, c, d

a, b, c, d, e = a, b, e, d, c

a, b, c, d, e = b, c, e, a, d

a, b, c, d, e = e, a, c, b, d

a, b, c, d, e = a, e, c, b, d

a, b, c, d, e = b, d, e, c, a

print(f"c = {c}")

def main(): # << START_OF_TRACE

execute_repl_trace()

<|frame_sep|>CWM Output Format (Execution Trace)(abbreviated)

<|call_sep|>{}<|action_sep|>def main(): # << START_OF_TRACE<|frame_sep|>

<|call_sep|>{"a":8,"b":4,"c":7,"d":8,"e":7}<|action_sep|>def execute_repl_trace():<|frame_sep|>

<|line_sep|>{"a":7,"b":4,"c":8,"d":8,"e":7}<|action_sep|>a, b, c, d, e = c, e, b, a, d<|frame_sep|>

...

<|line_sep|>{"a":7,"b":7,"c":8,"d":8,"e":4}<|action_sep|>print(f"c = {c}")<|frame_sep|>

<|return_sep|>{"a":7,"b":7,"c":8,"d":8,"e":4}<|action_sep|>print(f"c = {c}")<|arg_sep|>"None"<|frame_sep|>3.3 CWM Hallucinates Commands

As sequence length increases, CWM's accuracy drops. But why? Inspecting the errors reveals a surprising failure mode: the model hallucinates commands.

Rather than making small mistakes in state updates, CWM often generates an incorrect next command, predicting a swap that wasn't in the original sequence. Once this happens, all subsequent states become wrong because they're computed from a corrupted history (Figure 6).

CWM Baseline

CWM + Teacher Forcing

Figure 6: Action hallucination in CWM. (Left) Baseline: the model hallucinates

command 2 (c, a, b instead of b, a, c), producing incorrect state.

(Right) Teacher forcing: injecting ground-truth commands at each step yields correct state,

demonstrating the model can track state when given correct actions.

3.4 Teacher Forcing: CWM Can Track State

To decouple command generation from state tracking, we use teacher forcing: we feed the model the correct commands at each step, and only ask it to predict the resulting state. With teacher forcing, the correct intermediate state is injected after each command, breaking the error chain.

With teacher forcing, CWM maintains high accuracy even at 128 commands! This mechanism explains the large accuracy gap observed at longer trace lengths: at 64+ commands, baseline accuracy drops to 0% while teacher forcing maintains ~90%.

This tells us that when commands are correct, the model can reliably propagate state over long horizons. The dominant failure in the baseline setting is generating incorrect commands, not an inability to update state.

3.5 Dense Supervision: Mechanism and Trade-offs

The teacher forcing results confirm it: CWM's state-tracking ability comes from dense supervision, not architectural innovation. With reveal spacing = 1, the model never has to track state for more than one step. The explicit state reveals act as "checkpoints" that reset any accumulated error.

Table 2: Supervision density comparison

| Approach | Reveal Spacing | Supervision Density | Token Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard LLM | ∞ (no reveals) | None | Low |

| Sparse reveals | 4-8 | Low | Medium |

| CWM | 1 | Maximum | High |

3.6 The Trade-off

Dense supervision works, but it comes at a cost:

- Training: Requires execution traces with full state dumps, which are expensive to collect

- Inference: Generates many tokens for state representations, making it slower and more expensive

3.7 Architecture Matters for Sparse Supervision

CWM's success with dense supervision (reveal spacing = 1) raises a natural question: what happens when we can't afford such dense state reveals? This is where architecture becomes critical.

Sparse observation forces models to carry execution state over longer horizons without frequent “checkpoints”. Prior work suggests this is exactly where architectural inductive bias matters: recurrent and state-space models are natural candidates for stable state propagation under reduced observation.

4. Discussion & Conclusion

Transformer-based CWMs achieve strong baseline performance (85% on CruxEval, 91% on HumanEval) by using dense state supervision (full state reveals at every step). This sidesteps the need for sophisticated state-tracking mechanisms: the model never needs to track state across more than one operation. However, this approach has clear limitations: long-running programs can trigger trace truncation; and string-valued state is brittle under subword tokenization, causing deterministic string operations to fail and compounding sharply under string composition.

The key insight is that expressivity is not learnability. Dense traces can make local state updates easy to learn, but they also create token-intensive execution histories and do not resolve representation instability for strings. Future code world models will need supervision and state representations that are better aligned with program execution and data types.

References

- Jake Bruce, Michael Dennis, Ashley Edwards, Jack Parker-Holder, Yuge Shi, Edward Hughes, Matthew Lai, Aditi Mavalankar, Richie Steigerwald, et al. Genie: Generative Interactive Environments. 2024. arXiv:2402.15391 [cs.LG].

- FAIR CodeGen Team, Jade Copet, Quentin Carbonneaux, Gal Cohen, Jonas Gehring, Jacob Kahn, Jannik Kossen, Felix Kreuk, Emily McMilin, Michel Meyer, Yuxiang Wei, et al. CWM: An Open-Weights LLM for Research on Code Generation with World Models. 2025. arXiv:2510.02387 [cs.SE].

- Minsoo Kim, Yeonjoon Jung, Dohyeon Lee, Seung-won Hwang. PLM-based World Models for Text-based Games. EMNLP 2022, pp. 1324–1341.

- Wolfgang Lehrach, Daniel Hennes, Miguel Lazaro-Gredilla, Xinghua Lou, Carter Wendelken, Zun Li, Antoine Dedieu, Jordi Grau-Moya, Marc Lanctot, Atil Iscen, et al. Code World Models for General Game Playing. 2025. arXiv:2510.04542.

- Nicola Dainese, Matteo Merler, Minttu Alakuijala, Pekka Marttinen. Generating Code World Models with Large Language Models Guided by Monte Carlo Tree Search. NeurIPS 2024, vol. 37, pp. 60429–60474.

- Hao Tang, Darren Key, Kevin Ellis. WorldCoder: A Model-Based LLM Agent for Building World Models by Writing Code and Interacting with the Environment. NeurIPS 2024, vol. 37, pp. 70148–70212.

- William Merrill, Ashish Sabharwal. The Parallelism Tradeoff: Limitations of Log-Precision Transformers. NeurIPS 2023. arXiv:2207.00729.

- Bingbin Liu, Jordan T. Ash, Surbhi Goel, Akshay Krishnamurthy, Cyril Zhang. Transformers Learn Shortcuts to Automata. ICLR 2023. arXiv:2210.10749.

- Antonio Orvieto, Samuel L. Smith, Albert Gu, Anushan Fernando, Caglar Gulcehre, Razvan Pascanu, Soham De. Resurrecting Recurrent Neural Networks for Long Sequences. ICML 2023. arXiv:2303.06349.

- Lifan Yuan, Weize Chen, Yuchen Zhang, Ganqu Cui, Hanbin Wang, Ziming You, Ning Ding, Zhiyuan Liu, Maosong Sun, Hao Peng. From f(x) and g(x) to f(g(x)): LLMs Learn New Skills in RL by Composing Old Ones. 2025. arXiv:2509.25123.

- Alex Gu, Baptiste Rozière, Hugh Leather, Armando Solar-Lezama, Gabriel Synnaeve, Sida I. Wang. CruxEval: A Benchmark for Code Reasoning, Understanding and Execution. 2024. arXiv:2401.03065.

- Mark Chen, Jerry Tworek, Heewoo Jun, Qiming Yuan, Henrique Ponde de Oliveira Pinto, Jared Kaplan, Harri Edwards, Yuri Burda, Nicholas Joseph, Greg Brockman, et al. Evaluating Large Language Models Trained on Code. 2021. arXiv:2107.03374.

Resources

Citation

@article{rahmani2026debugging,

title={Debugging code world models},

author={Rahmani, Babak},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:2602.07672},

year={2026},

url={https://arxiv.org/abs/2602.07672}

}

Comments